What’s the diagnosis?

A man with a worsening rash of scaly plaques

Case presentation

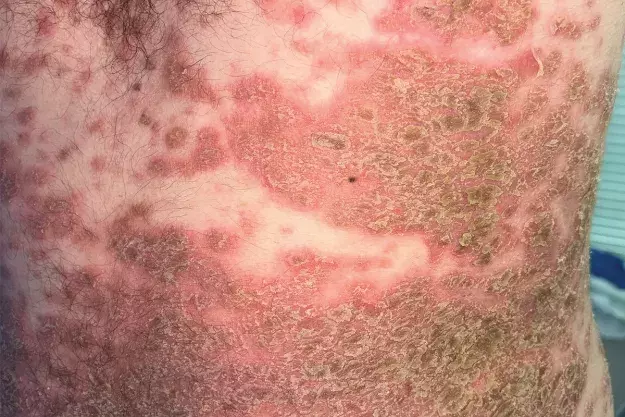

A 28-year-old man presents to the emergency department with a widespread rash consisting of erythematous crusted plaques (Figures 1a and b). The lesions first appeared 18 months ago and were initially confined to his chest, neck and back with minimal facial involvement. The rash has been treated with azathioprine for the past month, with up-titration a few days before presentation. However, the lesions have recently spread and are associated with considerable pain.

The patient is otherwise well and not taking any other regular medications. He has presented because of worsening symptoms and difficulty coping at home.

On examination, a widespread rash of erythematous plaques with overlying crust and scale is observed, predominantly overlying the seborrhoeic distribution. Involved areas include the chest, neck, abdomen, axillae and upper back. His face and postauricular areas are also affected; findings are similar for the frontal hairline. There are plaques located in the groin that are thick, macerated and malodorous. The lower limbs are affected to a lesser extent. The patient is systemically stable but feels unwell with subjective chills.

Differential diagnoses

Conditions to consider among the differential diagnoses include the following.

Bullous impetigo

Impetigo is a highly contagious bacterial skin infection that is most often seen in children but can occur at any age.1,2 It may be bullous or non-bullous. The less common variant, bullous impetigo, is caused by a Staphylococcus that produces an exfoliative toxin.

Clinically, bullous impetigo often begins as erythematous macules that evolve into vesicopustules, which become confluent, resulting in bullae.1 These rupture easily to release serous fluid, leaving a characteristic yellow crust that often has a collarette of scale.1,2 The lesions are usually located on the face, trunk, buttocks, extremities and perineal areas. Associated fever, malaise and lymphadenopathy may occur.2

Impetigo is usually a clinical diagnosis. Surface swabs for bacterial culture and sensitivity testing are only required if the disease is recurrent or resistant strains are suspected.3 Patients with recurrent infections may require eradication strategies for staphylococcal carriage.

This was not the correct diagnosis for the case patient. The vegetative appearance of some of his lesions (i.e. raised granular or crusting with multiple projections) was similar to the ruptured blisters of bullous impetigo; however, there was no yellow crusting and no vesicopustules. Surface swabs were taken and results returned no infection. In addition, the disease was more extensive and present for longer than would be expected for bullous impetigo.

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) is most common in women who are aged in their third or fourth decades but can be seen in patients of any race, gender or age.4,5 The condition may occur independent of systemic lupus erythematosus.

SCLE usually presents on sun-exposed areas as symmetrical, erythematous patches that may be papulosquamous or annular.4,5 The condition is caused by a combination of genetic and environmental factors, such as exposure to ultraviolet radiation; about 20 to 40% of cases are drug-induced – common culprits include terbinafine, calcium channel blockers and thiazides.6

SCLE is generally a clinical diagnosis but can be confirmed with biopsies for histopathology and direct immunofluorescence testing.5 Blood tests for markers of inflammation and autoantibodies (e.g. ANA and dsDNA tests) can also be completed to screen for systemic lupus erythematosus.4

For the case patient, SCLE was not a likely diagnosis because his rash was not photodistributed and its overlying crust and scale were not characteristic for the condition. He was not the common demographic and had no identified environmental triggers associated with this disease.

Seborrhoeic dermatitis

Seborrhoeic dermatitis is a common inflammatory skin condition that affects about 3 to 12% of the population.7,8 Although the exact aetiology is unclear, it is thought to involve a dysregulated immune response to Malassezia, a commensal yeast that occurs on healthy skin, especially areas that are rich in sebaceous glands.9 A relapsing form of dermatitis, it presents as yellow, greasy scale on an erythematous background, often affecting the face (especially the eyebrows and paranasal grooves), scalp and trunk.8 The condition has a biphasic incidence, with peaks during the stages of infancy and late adolescence.8 Seborrhoeic dermatitis is a common condition and diagnosed clinically.

This was not the correct diagnosis for the case patient. Although his rash was seborrhoeic in distribution, its morphology was different to classic seborrhoeic dermatitis, without the lighter greasy scale and facial distribution.

Subcorneal pustular dermatosis

Subcorneal pustular dermatosis (SPD), also known as Sneddon-Wilkinson disease, is a rare, benign and chronically relapsing disorder characterised by sterile pustules that appear in crops over months or years.10 Annular plaques with superficial flaccid pustules on the border are usually found in intertriginous areas and may extend to the torso or body folds.11 The classic feature is ‘half-and-half’ pustules containing a fluid that separates into a clear upper portion and a purulent lower portion; these are replaced by irregular scales; but new pustules recur in a few weeks or months. SPD usually presents in middle-aged adults and has a female predominance.

Diagnosis of SPD is based on clinical findings and biopsy. Histological examination shows neutrophilic infiltration and occasional eosinophils in the subcorneal layer of the epidermis; the corneal layer may be separated from the rest of the epidermis, with no appreciable dermal changes.12

SPD is classified as a neutrophilic dermatosis. The aetiology of the disease remains unclear, however, and some researchers have postulated it to be a variant of psoriasis.12 SPD is associated with other conditions, including multiple myeloma, IgA monoclonal gammopathy and pyoderma gangrenosum.10

For the case patient, SPD was a less likely diagnosis because there was a lack of pustules in his rash. In addition, its seborrhoeic distribution was not typical of the disease.

Pemphigus vulgaris

Pemphigus vulgaris is one of two main variants of pemphigus, a class of rare autoimmune blistering diseases.13 About 70% of pemphigus cases are attributed to pemphigus vulgaris, which is characterised by painful erosions and blisters in the mucous membranes and skin.14 In this condition, IgG autoantibodies adhere to desmoglein-3, a protein in epidermal desmosomes that is essential for maintaining skin integrity.13 This leads to separation of keratinocytes with space being replaced by fluid, which is clinically seen as a blister.14

Most patients with pemphigus vulgaris first present with lesions of the mucous membranes. After a few weeks or months, flaccid blisters develop on the skin.14 These blisters are often located on the face, scalp, back and upper chest, and rupture easily to leave painful and pruritic erosions.14 Pemphigus vulgaris is more prevalent among women than men and in people of Indian and Jewish ancestry.15 Patients usually present between 40 and 60 years of age.15

This was not the correct diagnosis for the case patient. Although his plaques were scaly and erythematous, there was no mucosal involvement.

Pemphigus foliaceus

This is the correct diagnosis. Pemphigus foliaceus, the other main variant of pemphigus, is less common and less severe than pemphigus vulgaris and is characterised by superficial blisters, erosions and crusts on the skin without involvement of the mucous membranes.16 In this condition, autoantibodies are produced against desmoglein-1, a protein in keratinocytes near the top of the epidermis – this results in superficial blisters that rupture very easily, leaving shallow erosions associated with a burning sensation or pain.17 The lesions are usually located on the scalp, face and upper trunk, and are generally crusty and scaly on an inflamed, erythematous base.17

Pemphigus foliaceus often presents in adulthood, usually around the fifth decade, but cases have occurred in childhood. It is endemic in some rural areas in South America, where it has the local name fogo selvagem, which can be translated to ‘wild fire’.13 The exact aetiology is unclear but is thought to involve an interplay between genetic and environmental factors, with some medications that contain thiol groups, such as captopril and penicillamine, being implicated.16,18 About half of thiol-induced cases resolve on cessation of the offending medication.18

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of pemphigus foliaceus requires two biopsies: a lesional specimen for histopathology and a perilesional specimen for direct immunofluorescence testing.16 Pemphigus foliaceus is confirmed by the presence of intraepidermal, subcorneal blistering in the lesional specimen and direct immunofluorescence showing IgG deposition in the perilesional specimen.16,19

Biopsies are essential for differentiating pemphigus vulgaris from pemphigus foliaceus. Histopathology for pemphigus vulgaris demonstrates suprabasilar acantholysis, and the difference in location of this split forms the key distinction between the two variants.19

Management

The initial management of pemphigus foliaceus generally consists of systemic corticosteroids with the aim of achieving rapid disease control, although topical corticosteroids may be the only modality required to treat mild disease.17 Timely review of medications is recommended, and any potential triggering drugs should be ceased.17 Once control has been achieved, corticosteroid-sparing agents may be used in conjunction to reduce corticosteroid dependency.20 The combination of intravenous rituximab and systemic corticosteroids has been shown to have greater efficacy in patients who have moderate to severe pemphigus than using these agents separately and is available at specialised centres.19

Outcome

The case patient was diagnosed with an acute flare of pemphigus foliaceus. About 18 months prior to this presentation, he had been diagnosed with pemphigus foliaceus, which was confirmed by biopsies and the presence of desmoglein-1 antibodies. He was initially managed with topical corticosteroids, oral prednisone and mycophenolate mofetil 1 g twice daily. The corticosteroid-sparing agent had been switched to azathioprine 50 mg daily one month ago to achieve better disease control and was up-titrated to 150 mg daily a few days before his current presentation. The flare could possibly be attributable to recent changes in immunosuppressive medications and to a respiratory tract infection experienced during the past month.

The patient was admitted to a tertiary centre. He was treated with prednisolone 25 mg daily with a potent topical corticosteroid (betamethasone dipropionate 0.05% ointment) under wet dressings. Due to the severity of the flare, intravenous rituximab (two doses of 1 g each, given two weeks apart) was also administered. In addition, he was treated with oral trimethoprim 160 mg/sulfamethoxazole 800 mg three times weekly for Pneumocystis jirovecii prophylaxis. His regular dose of azathioprine was continued.

The patient was discharged after five days, with his second dose of rituximab administered as an outpatient. The prednisolone was reduced to a baseline of 5 mg daily as his rash continued to improve. He was returned to the care of his community dermatologist, with regular reviews to monitor the continuing efficacy and immunosuppression associated with rituximab. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. Robinson C, Jones J, Chachula L, Neiner J. Bullous impetigo: a mimicker of immune-mediated dermatoses. Mil Med 2023; 188: e1332-1334.

2. Quirke K. Impetigo. DermNet; 2022. Available online at: https://dermnetnz.org/topics/impetigo (accessed July 2025).

3. Johnson MK. Impetigo. Adv Emerg Nurs J 2020; 42: 262-269.

4. Saracino A. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Australian College of Dermatologists; 2024. Available online at: https://www.dermcoll.edu.au/atoz/cutaneous-lupus-erythematosus/ (accessed July 2025).

5. Jatwani S, Hearth-Holmes MP. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024.

6. Gordon H, Oakley A. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. DermNet; 2023 [updated by Coulson I]. Available online at: https://dermnetnz.org/topics/subacute-cutaneous-lupus-erythematosus (accessed July 2025).

7. Karakadze MA, Hirt PA, Wikramanayake TC. The genetic basis of seborrhoeic dermatitis: a review.

J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2018; 32: 529-536.

8. Bholah NG, Oakley A. Seborrhoeic dermatitis. DermNet; 2024 [updated by Gomez J]. Available online at: https://dermnetnz.org/topics/seborrhoeic-dermatitis (accessed July 2025).

9. Aspres N. Seborrhoeic dermatitis and cradle cap. Australian College of Dermatologists; 2020. Available online at: https://www.dermcoll.edu.au/atoz/seborrhoeic-dermatitis-cradle-cap/ (accessed July 2025).

10. Hill S. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis. DermNet; 2006. Available online at: https://dermnetnz.org/topics/subcorneal-pustular-dermatosis (accessed July 2025).

11. Psoriasis [chapter 6]. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, Ko CJ, eds. Dermatology essentials. 2nd ed. London UK: Elsevier; 2022.

12. Watts PJ, Khachemoune A. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis: a review of 30 years of progress. Am

J Clin Dermatol 2016; 17: 653-671.

13. Schmidt E, Kasperkiewicz M, Joly P. Pemphigus. Lancet 2019; 394: 882-894.

14. Ngan V, Oakley A. Pemphigus vulgaris. DermNet; 2022 [updated by Shakeel M]. Available online at: https://dermnetnz.org/topics/pemphigus-vulgaris (accessed July 2025).

15. Porro AM, Seque CA, Ferreira MCC, Enokihara MMSES. Pemphigus vulgaris. An Bras Dermatol 2019; 94: 264-278.

16. Murrell D. Pemphigus foliaceus. Australian College of Dermatologists; 2023. Available online at: https://www.dermcoll.edu.au/atoz/pemphigus-foliaceus/ (accessed July 2025).

17. Ngan V. Pemphigus foliaceus. DermNet; 2022 [updated by Shakeel M]. Available online at: https://dermnetnz.org/topics/pemphigus-foliaceus (accessed July 2025).

18. Wu B, Oakley A. Drug-induced pemphigus. DermNet; 2017. Available online at: https://dermnetnz.org/topics/drug-induced-pemphigus (accessed July 2025).

19. Stumpf N, Huang S, Hall LD, Hsu S. Differentiating pemphigus foliaceus from pemphigus vulgaris in clinical practice. Cureus 2021; 13: e17889.

20. Hertl M, Geller S. Initial management of pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus. UpToDate; 2025.

Pemphigus