What’s the diagnosis?

Widespread rash in a 6-year-old boy

Case presentation

A 6-year-old boy presents with a rash that appeared two months ago and spread to involve his whole skin within a week. It is most severe on his trunk (Figure 1) but also involves his face and limbs.

At this presentation, the rash has a polymorphic appearance consisting of papules, vesicles and small scaly macules; there are some areas of pigment loss. At a previous presentation, the rash had been vesicular and thought by the doctor who assessed the patient at this stage to probably be chickenpox.

Currently, the rash is not severely itchy and does not wake the patient at night. Nevertheless, his mother is concerned about it and the boy has been sent home from school by teachers who have been worried that he may have a contagious condition. The rash has persisted despite treatment with antifungal creams, oral antibiotics and topical corticosteroids.

Differential diagnosis

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis include the following.

- Guttate psoriasis. This is a very common form of psoriasis in young children and is usually precipitated by a streptococcal throat infection. The lesions are monomorphous, red and scaly, but there is never a vesicular component. This condition can be of sudden onset and persist until actively treated. Children usually have other signs of psoriasis. Guttate psoriasis has a strong genetic component and there is often a family history.

- Pityriasis rosea. The cause of pityriasis rosea is controversial, but most experts agree that it behaves like a viral exanthem.1 However, it may be a ‘reaction pattern’ with more than one viral cause. The classic presentation is sudden onset of a single lesion (‘herald patch’), which is followed seven to 14 days later by smaller similar scaly patches that can last up to six weeks. Patches are erythematous and ovoid to circular in shape, with a ‘collarette of scale’. Itch is usually absent. Many variants of pityriasis rosea have been described, including a vesicular one, but the condition is invariably self-limiting.

- Lichen planus. Lichen planus is not uncommon in adults but it is an extremely rare eruption in children. Its protean manifestations include vesicles, but the most common presentation is multiple, flat-topped, nonscaly papules.

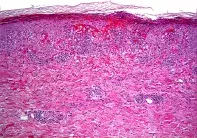

- Pityriasis lichenoides chronica (PLC). This is the correct diagnosis in the case described above. PLC is a relatively uncommon condition of unknown aetiology, with clinical presentations that range from acute to very chronic. In the vesicular phase, it is often referred to as pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acute (PLEVA). It has been hypothesised that the condition represents a hypersensitivity reaction to a viral antigen.2

Diagnosis

PLC has a classic appearance on skin biopsy, which can be used to confirm a clinical diagnosis (Figure 2). However, a confident diagnosis can be made by dermatologists, particularly in children, based on the combination of scaly macules and papules, as well as hypopigmentation and vesicles when present. The uncommon nature of the rash makes it difficult for GPs to identify.

The initial rash of PLC is papulovesicular and it is often mistaken for chickenpox. However, chickenpox resolves in a few weeks, whereas the lesions of PLC evolve to crusted papules associated with pigment change.

Management

The rash of PLC, although harmless, is often very persistent and can last from six weeks to months or years. It has been reported to respond to prolonged treatment with erythromycin and tetracycline, but UVB phototherapy is more reliable. Oral retinoids are useful in severe, persistent cases.

References

1. Drago F, Broccolo F, Rebora A. Pityriasis rosea: an update with a critical appraisal of its possible herpesviral etiology. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009; 61: 303-318.

2. Ersoy-Evans S, Greco MF, Mancini AJ, Subaşi N, Paller AS. Pityriasis lichenoides in childhood: a retrospective review of 124 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007; 56: 205-210.

Skin lesions